In any event, I had a birthday recently (yes, I feel old!) and one of my daughters gave me a copy of a book by Steve Roth called Hamlet: The Undiscovered Country. Okay, I had run across a reference to it and had put it on my “wish” list, but anyone who knows me knows that I am an even bigger Hamlet nut than I am a general Shakespeare one, so the problem is what do I not already have, not would I find this of interest. The book was originally copyrighted in 2009, but the Second Edition (which I have) is dated 2013, so it’s a fairly recent publication and I had not heard of it until August, when I think I ran across it on Amazon.

While I don’t think that Roth’s book answers all of the possible questions which can arise regarding this play, it does offer some interesting takes on some of them, most notably the question of Hamlet’s age. “But,” you say, “there’s no question of Hamlet’s age. The gravedigger tells us that he is thirty, so that’s not a question worth pursuing.” After reading Roth’s discussion, however, I’m not sure it’s all that cut and dried.

As Roth points out, when the gravedigger speaks about how long he has been a grave maker, the First Folio has him say that he started on the same day that Prince Hamlet was born, saying “Why heere in Denmarke: I have bin sixeteene here, man and Boy thirty yeares.” Yes, I DID check this in my facsimile First Folio. Many more recent editors have changed that “sixeteene” to “sexton,” but that word is spelled correctly just a few lines earlier when Hamlet says, in reference to one of the skulls the gravedigger has tossed up that it is being “…knocked about the mazzard with a sexton's spade….”(emphasis added, RSB) The word “sexton” (spelled that way) also shows up in numerous places in other plays, which suggests that it was a commonly used term (with that spelling) in the period of Shakespeare’s writing, so there is little logical reason to believe that the fairly often used spelling of “sixeteene” to refer to the number after fifteen doesn’t, even in this case, in fact, refer to that number. Roth suggests that the gravedigger is really saying that he (the gravedigger) is thirty and started sixteen years ago, which would make Hamlet really only sixteen, if he was born on the day the gravedigger started. I found this argument (Roth develops it a good deal further than I’m going to take it) quite interesting for a variety of reasons.

1.) If Hamlet is thirty, why is he still in school? Most aristocratic youth in Elizabethan England went to college as teenagers, as I remember what I have read, and had graduated by the age most start today. A Master’s degree at age twenty would not have been unheard of, perhaps even fairly common, for those who were going that far in their education. So, why does Claudius say,

“ For your intent

In going back to school in Wittenberg,

It is most retrograde to our desire:”

If Hamlet is really thirty, what was he doing at school? That would by quite unusual, but it’s just passed off as routinely as if Laertes was also about the same age and wishing to go back to school in France. It’s not unreasonable for men to wish to finish their education, but for a thirty-year old to still be a student at this time would have been quite unusual and there is nothing to suggest that he was on the faculty, which would have been inappropriate for a member of a royal family in any event.

2.) Also, if Hamlet was thirty, why does he carry on with Ophelia like a sophomoric schoolboy, at least apparently, and at least some of the time? Aristocratic males were usually married by early to mid-twenties, and aristocratic females were often wed by fifteen, what with the need for heirs and the mortality rate of infants (and new mothers). So, it seems to me that the idea of Ophelia being a teenager (maybe even a youngish teenager) makes a lot of sense for a good many reasons. Hamlet’s apparent lack of sophistication in dealing with matters of the heart (not terribly surprising in a time when aristocratic weddings had more to do with politics than affection) are also made easier to understand, if he is more youthful, as opposed to a dirty old man.

3.) There is also the question of why Claudius, the old king’s brother, has become king instead of his son, Hamlet. We tend to think of monarchies as being inherited, but we (I, at least) don’t know if that was standard in Denmark at that time (at least as early as the 1200s, if the source is, in fact, Saxo Grammaticus’ version of the earlier [Old Norse?] story, as most believe). There is some reason to believe that primogeniture was NOT the standard /practice procedure of that time the original story appeared and that kings were, in fact, often elected by a council of the senior nobility, which seems to be referred to in the script in several places. Plus, England had, fairly recently, gone through a “regency” period during the reign of Edward VI, so the idea of a king too young to be trusted with power wasn’t unheard of, especially considering that it is established (in the play) that there was a distinct possibility of war (preparations are being made, ambassadors being sent, etc.) which makes the idea of not electing a not-yet-fully educated young man as king in times of questionable national security fairly reasonable.

4.) Then, we have the question as to why Claudius makes such a point of stating “…let the world take note, You are the most immediate to our throne; …,” which seems to establish the idea that Hamlet should become the king after him. I would argue that it just might be important that this is his decree, not an election of the heir. If Hamlet is sixteen, then it’s not unreasonable to believe that Gertrude could be about thirty, or just a bit older. That would suggest that she might be fully capable of producing an heir for Claudius, who is under no restriction from changing his mind about Hamlet’s place in his proposed line of succession. However, that would make the play MUCH more about determining the legitimacy of Claudius’ kingship (over Hamlet’s) than I (personally) think is the case, but it does seem explain a couple of awkward bits in the script, so it might be worth thinking about.

To wrap this up, I do NOT think that Roth has solved all of the questions which the script of Hamlet poses. I’m not sure I’d go so far as to say that he has solved any of them. Like so many others, however, he has made some interesting points and has contributed them to the general discussion of the play. Some of his ideas, like Hamlet being younger than is usually accepted, I find make a great deal of sense and are highly worth considering. Some of the others, I’m not sure I buy, but I would suggest that this is very much a book worth looking at for fans of Hamlet.

I think I’ll quit here for this posting. I’ll try to be a bit more regular about posting than I have been during the last couple of months. The unpleasantness of the election just made it harder than usual to focus on the sort of ideas that I can enjoy writing about. And, since I do this because I enjoy it, it was even harder than usual to do.

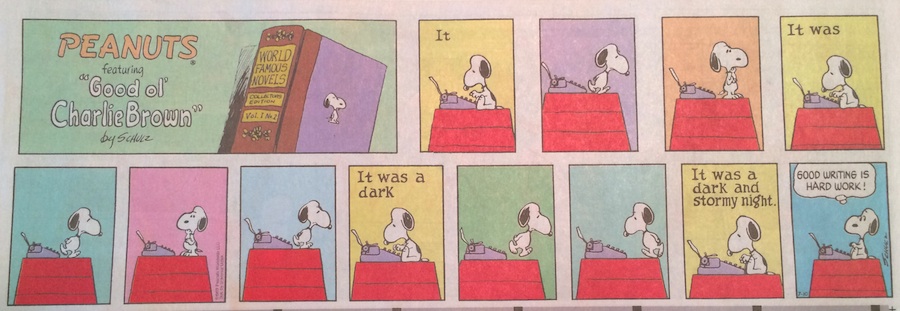

As I often said to my thesis students, good writing is never really easy (see below):

LLAP

RSS Feed

RSS Feed