Then, I’m also old enough to remember when Facebook first appeared (I think it was the earliest manifestation of social media) and everyone wondered how there could be a business model based on providing a “free” service which (at that time) had virtually no advertising. As I remember, for the first several years, Facebook had virtually no income and its demise was regularly announced as imminent, although some advertising did start to appear on it. Of course, what we now understand is that this was a time of getting established in the market and starting to collect data which would allow the assembling of a socio-geo-demographic picture of Facebook users sufficient to be able to allow highly sophisticated targeting of advertising to those users who would be most likely to be susceptible to it.

While I was teaching, I became quite concerned about the nature and quantity of personal information which I understood my students were sharing on social media mostly because (having been around in the earliest days of the internet) I knew that, once something hit an internet server (which happens extremely early in the process of internet use), it is almost impossible for it ever to be removed. Yes, one can “delete” whatever has been posted, but how can one be assured that she/he had deleted it from every server that information has encountered prior to ANY backup occurring? The answer is that one can’t. This means that ANYTHING one puts on the internet could be retrieved by someone who wants badly enough to find it. I worried about that for my students.

What I long suspected, and have had confirmed recently, is that what Facebook (along with many other creators of “free” apps, like Google, and a bunch of others) was doing was keeping track of who was doing what, touching what topics, looking at what websites, etc., etc., and collecting this sort of data for the purpose of selling access to it for purposes of targeting advertising. Now, there is nothing new about that. Advertising has always been targeted to try to reach those believed to be most likely to respond to the ad. Apple’s iTunes uses such techniques to “suggest” music which I might be interested in based on previous choices. Barnes and Noble frequently sends me emails suggesting that; “Since you bought book “X,” you might be interested in book “Y.” And the list goes on. These are choices which I make, however. I am not required to give B&N my email address in order to do business with them. I don’t have to use iTunes. In fact, I’ve never actually bought anything from it (music, books or apps), although I have used it to play music, listen to audio books, and obtain free apps.

We are now coming to a greater understanding that the collection of personal data to be used for commercial purposes is the whole point of some apps and that this sort of thing can easily be abused, especially by using data collected over social media to send us advertising which is disguised as NOT being ads. As Madeleine Albright expresses it in her new book Fascism: A Warning, this technology has “…provided both the blessing of a more informed public and the curse of a misinformed one – men and women who are sure they know the truth because of what they have seen or been told on social media. The advantage of a free press is diminished when anyone can claim to be an objective journalist, then disseminate narratives conjured out of thin air to make others believe rubbish. The tactic is effective because people sitting at home or tapping away in a coffee shop often have no reliable way to determine whether the source is legitimate, a foreign government, a freelance impostor, or a malicious bot.” (p. 114.)

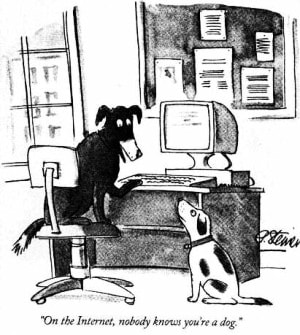

As an aside, I am reminded of an extremely early cartoon about the internet which seems appropriate here.

I find it particularly worrisome that this sort of “information” is not always revealed to be, in fact, advertising (propaganda). And, due in part to the fact that law has been struggling to try to deal with the tremendous volume of “information” on the internet, social media can be used to disseminate information which may be difficult or impossible to separate from advertising. This is further complicated by the fact that there is no requirement, or incentive, to reveal, let alone substantiate, the sources of such information. Since selling advertising (which may not appear to be advertising) is what supports these “free” apps, it doesn’t appear to be going too far to come to the conclusion, as Steve Wozniak recently did, “… with Facebook, you are the product.” (emphasis added, RSB)

That is, Facebook (and others, including, I believe, other social media systems and many browsers) makes its money by collecting as much information as it can about its users and selling that information (or their knowledge of it) to help their advertisers (and who knows what others) to target audiences for various purposes, while, apparently taking few steps to make sure that there is any revelation of the fact that they are collecting this information, or that they are using it for their own commercial purposes. Of greatest concern, at least to me, is their apparent lack of real interest in protecting their user data or making sure that it is not misappropriated or used by others for potentially improper purposes. (Yes, I know that “privacy settings” do exist, but I understand that they have been complicated to set, difficult to find and, apparently, inadequately protected.)

Newspapers and television advertising is required by law to be identified as advertising and the sponsors are required to be identified. (Even if various “patriotic” sounding PACs do not have to reveal the sources of their seemingly unlimited funding, thanks to “Citizens United.”) It’s true that this revelation of sources IS often pretty minimal, but it IS there. The traditional media (newspapers, magazines and broadcast radio and TV) has always been allowed to have an “editorial policy” which allowed them to publish their corporate opinions, but this was supposed to be confined to editorials, columns and specific commentary. This has become somewhat muddied with the advent of “cable” news agencies, which, since they don’t use the “publicly owned" airwaves, have much greater freedom to take a much wider editorial stance. But, even there, identified advertising is treated much as it is by more traditional media.

Be that as it may, I have very little desire to have my personal opinions harvested for someone else’s commercial purposes without my knowledge or desire. Historically, so called “privacy” settings have been complex and have required a good deal of savvy (and time) to set up in order to not be exposed to what I see as an undesirable invasion of my privacy. I actually have less of a problem with those annoying telephone calls seeking me to respond to an opinion survey, although I don’t appreciate having my life interrupted by them and almost always simply hang up.

I feel that my opinions are MY opinions and I feel I should have the right to share them as I see fit and with whom I wish. I am aware that folks who want to badly enough can probably determine fairly accurately how I feel about many things based on public records, or other sources over which I have only some control over, such as this blog, but I have no desire to make it any easier for folks to “harvest” data about me in order to provide them with a source of income, especially when I have little confidence that they won’t use MY data for purposes which I may not approve of or appreciate.

Life’s too short (and my blood pressure’s too high) for that sort of aggravation. After all, I would just like to be left alone to--

LLAP

RSS Feed

RSS Feed