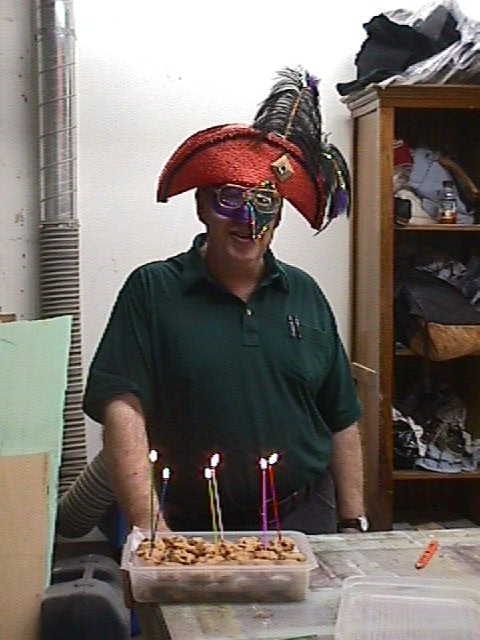

SEE! Even I CAN be a bit silly.

|

Just to prove that I'm not serious ALL the time, I post this picture. It was taken in the old scene shop in Stillwell (next to the Niggli Theatre where IT is now) a number of years ago. As I remember it, it was my birthday and Bonnie brought a batch of cupcakes to the shop to celebrate. I've never been sure, but I think that she and my shop assistants arranged for the silly hat to be available, but I don't really know how much advance "plotting and planning" went into this. Anyway, it's a fond memory and this picture reminds me of Sarah, Serenity, Joe, Scott and Jeff.

SEE! Even I CAN be a bit silly.

0 Comments

I think it was Barry Goldwater who said: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” It may seem odd to some, but I tend to agree with this. Defending liberty and pursuing justice are important to me. As is frequently the case, however, slogans (like that one) skim over the details and tend to be somewhat meaningless without adequate definition of the terms involved.

For example, I’ve indicated before that I am a strong supporter of Freedom of Speech. I think that’s a true statement. However, I am well aware of the fact that MY freedom of speech ends when it interferes with YOURS, or when it endangers the public at large. Thus, I can really only enjoy the right to speak my mind when I grant others the right to disagree, and/or don’t endanger others (the classic illegal “yelling ‘Fire’ in a crowded theatre” scenario). That means that “Freedom of Speech” is not an absolute right. I would suggest that just as I support freedom of speech, I support the notion of freedom of religion. Again, however, I think that there are limits, and that they are much the same as for freedom of speech. That means that I am free to believe that MY religion is the only “correct” one, but I am not free to ACT on that belief in attempting to shut off YOUR right to believe that that is the case for the beliefs you espouse. Nor would it be proper for me to try to make laws which support my religious positions at the expense of yours. According to Wikipedia: “Extremism (represented on both sides of the political spectrum) is an ideology (particularly in politics or religion), considered to be far outside the mainstream attitudes of a society or to violate common moral standards.” (emphasis added) What concerns me is that I think we, as a society, may be getting in the habit of using this term simply as a way of referring to those we disagree with and without considering the actual definition. I think I understand why this may be the case (it’s quick and easy, like slogans) but it may be putting us in the position of being just as extreme as those we would condemn. I will admit that the definition of extremism does require some careful thought as it creates a number of problems if we are going to use the term accurately, as we probably should. The first problem is that we must attempt to define the “mainstream attitudes of a society….” Whose society? Which one? How can we meaningfully define “society?” We might be able to do that, at least to some extent, when we talk about a single country, but I’m not sure it’s really possible when that country is as large and diverse as the United States. One doesn’t have to look very hard to note that there are differences in social attitudes between rich and poor, urban and rural, geographic regions, etc., to say nothing of the traditional differences between young and old, male and female, etc. And, we haven’t yet touched on the racial, religious, and other differences which seem to be of considerable importance to many people. So, we seem to have a real problem in simply trying to define “mainstream attitudes” in a way on which all could agree, except, perhaps, on a VERY local level. We MAY have an even more difficult time when we try to establish “common moral standards.” I think the difficulty here lies in the fact that many, probably most, of us look to our religious beliefs for the basis of morality. Hence, there seems to be a common assumption that OUR religious/moral background is (or should be) accepted as the basis for ALL “moral standards.” This is a difficulty because, while many of us MAY have similar religious/moral backgrounds, the fact is that we don’t have identical ones. Something as simple as the Ten Commandments can create problems…. Personally, I have little difficulty with commandments V-X. The ideas of: “honoring your parents;” “not killing;” “not committing adultery;” “not stealing;” “not lying;” and, “not coveting another’s house, spouse or possessions” seem to me to make a lot of sense as a reasonable basis for having a peaceful society. Commandments I through IV (as they are commonly listed) are somewhat more problematic because they seem to speak rather strictly in support of a specific group of religions which are based on the book which contains these “commandments.” It might be worth noting that that book (the Old Testament) contains what are claimed to be the founding principles of Judaism, Christianity and Islam (the religions of “the book”). Based on some VERY cursory research, these ideas (all ten) would appear to be common to something just a bit over 50% of those who espouse a religion. Of course, that’s a long way from universal agreement, especially if we include the entire world as our society, which seems like a good idea, given the realities of present day life. But, even if we assume that commandments V through X represent ideas which we all could agree on, the fact is that we don’t actually follow them in practice. “Thou shalt not kill” is a pretty definite statement and wouldn’t seem to allow much “wiggle room.” It simply says that killing is NOT okay. It makes no exclusion for killing under orders in the military, when engaged in the defense of a religious belief, or even in self-defense. Thus, we get around this “common moral standard” by making exceptions for police, the military, for defense of home and family, etc. However, some folks, apparently, would argue that killing is a proper way to enforce personal religious positions (like by killing abortion providers and justifying that by saying that their religious beliefs regarding the sanctity of the life of the “unborn” take precedence over civil law). That strikes me as just as extremist as killing a satirist for making fun of a religious leader. Imagine what could happen if we killed people for satirizing political leaders? Most of our humorists would be doomed! Goodbye to The Daily Show, Saturday Night Live and a lot more! The scary thing is that that HAS happened in history, and still does. I will refrain from discussing coveting, lying and stealing, especially since it’s income tax season. I don’t think it’s really necessary to state that violations of these “standards” are often excused with statements like “Everybody else does it,” “I’m just trying to avoid being ripped off,” especially at this time of year. Given the constant stories in the popular media, it would be hard to suggest that not committing adultery is really a widely held virtue, as it is, apparently, not disapproved of to the extent that it really hurts the success of a fair number of celebrities, at least if the tabloid press is to be believed. All this seems to suggest that finding “common moral standards” and “mainstream attitudes” may be more difficult that it first appears. My concern is that it appears that people of many religious persuasions have chosen to try to define acceptable attitudes and standards in terms of their own religious beliefs and then attempted to codify them into law. I think that that desire is understandable, but it seems highly dangerous. It’s dangerous because once we define a specific religion as “normal, legal, proper:” we are defining those values which are different as “abnormal, illegal, improper.” Then, we make it worse by adding some sort of verbal preface (Islamic, Fundamentalist, Radical, etc.) to THOSE values and define them as “wrong,” when the fact is that they simply are different. Once we do that, we (the “good” people) believe that we should have the right to try to shut them down because THEY are outside of the accepted norm (they are the extremists) and WE are not (we’re the normal people). I think that is a pretty extremist position, in, and of, itself. What makes this particularly dangerous is that it mixes religion into politics, which has been shown throughout all of Western history to have dangerous consequences. ALL religions, even subdivisions such as denominations, sects, etc. (at least every one I know anything about) maintain that IT (and only it) is the “complete, final, absolute TRUTH” and that any form of debate or discussion about that is not really possible. When that sort of attitude gets mixed into the political landscape, we are likely to have trouble. Churchill is claimed to have said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” I think he was probably correct. Personally, I’d suggest that the worst possible form of government is a theocracy. That’s not because I’m against religion, but because I abhor the notion that any specific set of religious beliefs can be established as the only acceptable option. I’d suggest that if you don’t support abortion because of your religious beliefs, fine: don’t have one. But, please don’t suggest that YOUR religious beliefs trump mine and deny me the right to have an option. If you are against same sex marriage, that is your right. But, since we have chosen to use the same term to refer to both a religious AND a legal (civic) relationship, I am hard pressed to figure out how YOUR religious beliefs should be allowed to interfere with someone else’s legal rights under the “equal protection” clause of the US Constitution just because your RELIGION may choose not to sanctify this relationship. I’m not going to suggest that you, or your religion, must support this within the confines of your religious community (church), but to act to deny legal protection in the civic arena, is unacceptably extreme, at least to me. I think the point here is that it’s become far too common for all sorts of political groups to adopt “religious” justifications for their actions or positions because that makes them unarguable. That may be comforting, but it seems highly unlikely to lead to any sort of peaceful resolution of the underlying questions because both sides are convinced that they are “right” and that their religious beliefs “prove” this. That being the case, no peaceful resolution is possible and one is justified in taking whatever actions one chooses to force the other side to accept a specific point of view as “Truth.” That seems to me to be a form of extremism of which far too many of us are guilty. Unfortunately, when people start doing this with guns, bombs, and terror, it seems unlikely that it’s ever going to encourage others to actually accept any particular set of beliefs. It seems far more likely just to contribute to the atmosphere of violence and distrust which we call extremism (but only when referring to somebody else’s actions). So, how do I propose resolving the problem of extremism? The fact is that I think it’s unlikely that it’s going to be resolved; especially as long as some people insist that only they have direct access to divine authority. A world which accepts that there might be many acceptable paths and is willing to discuss beliefs in a way which grants others the right to disagree might end extremism, but I’m sorry to say that I’m pretty pessimistic about that actually happening. Still, given that pessimists are surprised as often as optimists, but always pleasantly, it may not be too much to say that I still hope to be pleasantly surprised. I was watching the Othello episode from the second season of the PBS series Shakespeare Uncovered the other day and it struck me that, although we’d like to think that questions of race are something we theatre people have left behind, we might have to do some careful thinking about whether or not this is really true, and whether or not it should be at this point in history.

Many of us support the idea of “color-blind” casting (not paying attention to the color of an actor’s skin when casting) and I have to say that I think this is often a good idea. However, it would appear that this notion could be “difficult” when race might have been a consideration of the creator(s) of the piece. It seems hard to imagine a production of West Side Story, for example, which completely ignores the race of the members of the two gangs. When the conflict was between two Italian families in an Italian city (Romeo and Juliet), race wasn’t an issue. When it’s between “Puerto Ricans” and “Americans” we’re dealing with an entirely different situation where the physical appearance of the characters seems as though it could be of some importance. I think it’s hard to conceive of a production of Driving Miss Daisy which ignores the racial differences between the main characters. We really have to pay attention to these characters’ race, given the period and locale of the play and, probably of greater importance, because it is a part of the play’s point, as is their gender. On the other hand, I know people who are reluctant to mount productions of some Tennessee Williams plays (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, for example) simply because those plays have Negro servants as minor characters and such roles are now viewed as demeaning. I think that Williams was simply reflecting the reality of the times and places about which he was writing. While it might be possible to set such plays in different times and places (often done, especially with classics), it seems to me that one must be careful not to ignore historical reality in recreating a period on the stage. After all, a play IS a product of its time and place and one should be careful about tampering with a playwright’s intent, even if some details don’t reflect current social practices. It would seem to me that a major consideration should be whether the intent of the material is significantly altered by ignoring these sorts of realities which were a part the original mise en scene of the piece. For example, I’m not aware of any criticism of Downton Abbey because color-blind casting hasn’t been used in it. I think that’s a valid choice. Miller’s The Crucible probably needs an actress of color to play the role of Tituba both because the real Tituba was a slave AND because her race was a part of why she was accused of witchcraft. Of course, one can say that these are “historical fiction” so it would be inappropriate to introduce historical inaccuracies. I think that’s the point! A LOT of drama, maybe most, is “historical fiction” and the choice of the race of a character MAY have been as carefully thought out as any of the other choices made by the author. I think that this is a reality that we ignore to our (and the theatre’s) peril. I am, generally, a supporter of color-blind casting, but I have to acknowledge that there are times when an author has made a conscious choice for legitimate reasons. I think Williams was aware of the history of the locales where he placed a number of his plays and didn’t create the servant characters to demean African-Americans, but simply to reflect the reality of those times and places. As another example, it’s almost impossible, these days, to conceive of a production of Othello, without the assumption that it is necessary for an actor of African descent to play the lead character. The one major exception that I know of was a production with Sir Patrick Stewart playing the lead with an, otherwise, all black cast. Of course, this wasn’t ignoring race, simply reversing it, which seems a perfectly viable alternative approach to a play where race relations seem of some possible importance. However, I think that it’s truly sad that many people seem to be embarrassed by or otherwise feel the need to deprecate the Othello of Laurence Olivier because he played the role in rather obvious black makeup (which was much more of a “coal dust” black than anyone I’ve ever met). I think this makeup was an unfortunate choice on Olivier’s part, but it’s too bad that we write off this performance by one of the greatest Shakespearean actors of the 20th century because we don’t like his makeup. Of course, Othello was, in fact, written for a Caucasian actor (Richard Burbage). There’s a story (probably untrue) that Dick Burbage and Will Shakespeare got drunk one night and Burbage bragged that he could play anything that Will could write. The story goes on that Will then decided to challenge Burbage by proceeding to create Othello. It is a fact that none of the actors in Shakespeare’s company were black, or Moors, to be correct as to how the character is actually described, and many non-African actors have played the role over the play’s history. I have no problem with an actor of African heritage playing Othello. I think it’s a perfectly logical choice. Many folks have suggested that the role does seem to have been created with the “otherness” of Othello in mind as the important factor and race is one way Shakespeare emphasized that. But it seems a bit racist to limit the casting of this role exclusively along racial lines when this tale of jealousy leading to murder doesn’t really seem to puts its focus on race as the basis for those actions. So why then MUST this role be played by an actor of color? Should Shylock only be portrayed by a Jew? Could Hamlet, or Henry V, not be played by an actor of color just because these historical figures weren’t “black?” I don’t think so. Nobody I know of seems overly upset that Denzel Washington played Don Pedro in Branagh’s movie of Much Ado About Nothing. Why? I think it’s because that character’s race doesn’t seem to matter to the play. If he had been cast as Don John (the “bad” guy), however, I suspect the casting would have been questioned due to the seemingly racist idea of the “bad” guy being of color. I think that this leads to the idea that it’s generally wise to be careful about introducing the questions which still exist regarding race into a play where race isn’t an issue. It is probably unfortunate that we, as a society, have not progressed beyond the point where issues of race still exist, but I’m afraid that we haven’t. However, it seems to me that introducing such issues into a play when they aren’t of importance is unwise and should be avoided. I was taught that we should strive to present the playwright’s intention and, when we force ideas into our interpretation of the author’s work which alter that intention, we are treading on dangerous ground. A black Ophelia with a white Hamlet (which I saw done in a production at the American Shakespeare Center) doesn’t seem to distort the major issues of Hamlet. To me, and to many others, the play revolves around the revenge tradition. I suspect that such a choice might make it logical to have Polonius and Laertes also be of color (which was not done in that production), but that doesn’t seem to have any impact on the vengeance motif, and there didn’t seem to be any difficulty in the audience accepting the idea of this actor as part of a family which has a position of some importance in the Danish court. I, personally, have spent a fair amount of time working on an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in which I have tried to make provision so that a fair number of traditionally male roles could be played by females and where I have consciously suggested that a good deal of color and gender blind casting might be appropriate. I think that this could be appropriate for this play because I think this play is not about race, or gender, but what can happen when a government is changed through assassination and violence leading to civil war. I think this play really focuses on the motives of political leaders and the consequences of violence in politics. It’s very common to believe that plays reflect the issues of the times of their creation. Certainly race can be, and has been, a real issue in our society, at least at times. But, when race, or gender, isn’t an issue in a play, we should be careful not to make it one. I’m not sure that I have a simple answer to what I feel are legitimate concerns regarding race in casting almost any play. It is certainly true that color blind casting can be, and often is, accepted by many audiences. One can find a number of examples of “blended” families on television, etc. I think that’s as it should be. Still, I think that we do, commonly, pay some attention to the race of a character, so that that character’s race is a choice which should not be just ignored in casting. It’s a choice which can distort some plays, both historical and modern, in ways which don’t serve the play very well, or it can add considerably to the audience’s experience. Until we have a society in which race isn’t really an issue, I think we have to be somewhat careful about how we deal with it. Not to do so, risks what I think might be an unfortunate alteration of a playwright’s intent, and I think that’s not a good idea. |

Just personal comments about things which interest me (and might interest others). Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed