Shakespeare’s birth/death day, well, let’s see. Actually, it’s his presumed birthday, as nobody felt that such insignificant things as birthdays were really all THAT important in those days. Now, BAPTISMAL days WERE important, so we actually have records of that date in Bill’s case. (THAT date being April 26, 1564, according to the actual church records, copies of which may be viewed at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-Upon-Avon!) Now, various “scholars” have decided to assign the day three days before his baptism as his ACTUAL birthday, which IS a perfectly reasonable and plausible choice, considering the general practices of the times, but it is, of course, a rather arbitrary choice. It’ll do, however, since we don’t actually have real records, etc., AND it IS the same calendar day as the day he died (except for the year), AND it’s also St. George’s Day (George being the patron saint of England) so it “rounds out” Bill’s life nicely and neatly, which seems to make some scholars happy. Now, we can be pretty positive as to when Shakespeare died, as THAT day, apparently, was also of sufficient importance to actually be put into official records. Anyway, the day in question, April 23rd, will be upon us shortly, so the time seems appropriate for a few of my occasional comments regarding Shakespeare, considering that it DOES mark the 460th anniversary of (what we think was POSSIBLY his BIRTHDAY)!

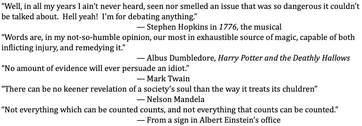

First, I should probably confess right off the bat that I DO THINK THAT THE MAN FROM STRATFORD ACTUALLY WROTE THE PLAYS FOR WHICH HE HAS, TRADITIONALLY, BEEN GIVEN CREDIT! I will, quite happily, admit that I can’t prove this, but given that this idea was virtually unchallenged for something around 200 years after his death, and not at all seriously until even later in the Nineteenth Century, suggests that there wasn’t (and isn’t) a great deal of actual evidence to support a challenge. Still, I will admit that it’s possible that he didn’t, actually, write them. However, it seems to me that notion would require that the most elaborate and comprehensive conspiracy in history had taken place, and was still continuing with a high degree of success. Now, I really don’t wish to get into THAT sort of unproductive discussion, especially since I don’t find it all that worthy of discussion.

The fact is that, regardless of whom you wish to argue was their author, I am extremely fond of many of Shakespeare’s works (some others, less so). I DO think they (as a group) are well worth the effort to actually read or see. Note that I am implying that I wish that people would actually read, or, preferably, SEE, the original works, not some “Shakespeare for Dummies in Modern Language” sort of thing. Yes, the English language has changed a bit from around 1600 to the present, but, there ARE people who have some actual expertise in the study of Shakespeare and his language who suggest that as much as 98% of Shakespeare’s words mean today, fairly exactly, what they meant 400 years ago when he wrote them. I would suggest that this implies that it should be quite possible for an English literate person to figure out what was intended by the original words chosen, especially since most GOOD editions do contain some “Notes,” or other assistance for the reader.

I would argue that such “Notes” should be taken with a certain degree of skepticism, however, and that many of Will’s works are well worth the effort to at least try to “puzzle out” their intent from the original words.

I don’t think it’s, generally, wise to rely on what “somebody” SAYS the words mean, no matter how good their credentials appear. I would argue that not relying on the original text requires, essentially, relying on a translation (interpretation) of the original words using the choices which someone other than that actual author suggests are “just as good” as the original words and are easier to understand. After all, many words can, and DO, have multiple meanings which rely on the specific context surrounding them for their specific meanings. It’s important to remember that ANY translation, in ANY language, MAY, quite easily, alter the context in such a way as to imply that one specific meaning is, in fact, the only acceptable one. That MAY not be the case, as it suggests that it’s okay to change the words (to make them more understandable). But, in fact, changing the words CAN, quite easily, change the meaning. That’s what is meant by “interpretation.” Now, interpretation MAY be essential for a specific production, but that doesn’t imply, or shouldn’t, that there are NO other options worthy of consideration.

To use my favorite example of how translation changes things (former students may remember this) I am told that En Attendant Godot (the French title) does NOT mean EXACTLY the same thing (at least to a French speaker) as the English title Waiting For Godot does. Without claiming ANY authority in the French language beyond Basic French in undergraduate school and a “Techniques of Translation” course which was required of Ph.D. candidates, my understanding is that “En Attendant” implies the notion that the person to which it is applied is “in the act, or state, of waiting”, which isn’t QUITE the same as is implied by the simple English statement, “Waiting.” I think it’s worth noting that Irish-born, native English-speaking, Beckett, wrote the original text of the play IN FRENCH, and then did his own TRANSLATION/REWORKING into the English version, but, “scholars” would (and have) argued that the two languages simply don’t translate exactly, as is true of MOST (if not ALL) languages.

I would suggest that “Translating” Shakespeare into “modern” English is, in fact, much like this. It is, in fact, a rewriting of the original. One still might end up with a good work, but it’s NOT, actually, the same. Yes, we theatre (and movie) people tamper with the originals when we cut them for production, or, otherwise, do anything except an unedited, “original practices” production, (which STILL wouldn’t be the same as the change in historical period (hence the context) would invalidate that notion. On the other hand, we, theatre people should (and, I believe, most do), make it quite clear from the get go that the specific production being presented represents OUR interpretation. Anything else would be, in my opinion, dishonest. I also like to think that most theatre people at least try to present an “honest” adaptation in their productions, even as they freely admit that they have made “choices” in their interpretation/understanding of specific words and/or phrases, etc.

I tend to agree with the quote from Sir Ian McKellen which I used back in Post 276 (not so long ago) which said:

If you start as a director by saying, ‘How can we make this play available to a bright 14-year-old who's prepared to give us two or three hours of their precious time,’ rather than saying, ‘Oh, everybody knows this play. How can we make it different?’… it won't inhibit you. You'll still get productions which vary and have a different emphasis and a different attitude, a different style, and that's absolutely fine. But I think it should always be done with a new audience in mind.

I think this idea allows for reasonable adaptation/interpretation, while also providing for the possibility of remaining true to the original author’s work.

I think this is also true of the actor’s work. A good deal of modern acting theory suggests the need for actor to perform “honestly,” or “with reality.” It’s heresy I know, but I tend to agree with Laurence Olivier when he said, “Acting is illusion, as much illusion as magic is, and not so much a matter of being real.” After all, theatre is MAKE BELIEVE. As I, have said many times; “The best script, the best cast, with the best setting and costumes, directed by the best director, is still just a bunch of people saying words and stumbling around in the dark until some techie turns on the lights.” That’s because theatre is NOT, by definition, “REAL!” In fact, it is much closer to the “reality” of children playing, than it is to actual “life.”

But many, maybe most, performers want to APPEAR, to create the illusion of being “real,” so they invent complicated “backstories” of their characters, and use other techniques to achieve this. Sir Ian commented on that notion during Episode 195 of the Shakespeare Unlimited podcast produced by the Folger Shakespeare Library;

The first word in Richard III is “now.” “Now is the winter of our discontent,” Shakespeare plays are happening in front of your eyes, “now.” He has this technique where he sometimes uses a chorus to tell you what’s been going on, but things have been going on and you’re in the middle. The play starts in the middle of life, “now.”

For an actor to worry too much about… how come at 80, he’s got three daughters? Could they have had the same mother, Queen Lear? And where is she? She’s never mentioned. Or, did he have two wives and did the second wife die in childbirth? And is Cordelia now of an age and looking like her mother when King Lear fell in love with her and married her? Well, you can invent all this, but it won’t really advance what the audience sees in the story. He’s not interested in the mother or mothers. I used to wear two wedding rings, for the alert, but it doesn’t matter.

Now, it might matter to the actor. It might make it easier for the actor to remember the mother of Cordelia as he looks into the young girl’s eyes. But you can’t start explaining all that to the audience, and if Shakespeare wanted you to, he would’ve put in the scene, the speech, the reminiscence which would’ve made for that clarity, which sometimes we as an actors, we can feel we’re missing.

So you just have to say, “Now,” and get on.

I hope this gives some people something to think about. I think it might be worth the effort.

On a lighter note, I ran across this a while back and hoped I’d find a place to use it. I think it’s funny, as well as true. Maybe you will, too.

Oh, well, enough of this, rambling, theatre talk. Go work on a play, act, direct, design, build one. It will be good for your soul. At least, go see one (even a GOOD movie version, will help), you’ll see!

I think the thing that allows most theatre people to maintain at least a certain level of optimism at all times is remembering that: “It’s ALWAYS opening night because this audience has never seen this performance of this production!” That’s a sort-of quote from a whole lot of theatre people (including me)!

I will be back in a couple of weeks,

🖖🏼 LLAP,

Dr. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed