I confess that the valuations are of some interest to me, but I do find the commentary regarding the creation of the various objects, their condition and provenance and how this item relates (or doesn’t) to similar sorts of things one might encounter to be of more interest than just the financial “value” of the item. After all, they don’t belong to me, so their value is only of general interest to me. Obviously, when one is speaking of “treasures” (valuable, or not) which are a part of, say, a family’s traditions, the monetary value is often of less importance than the fact that the item has been a part of the family tradition and folklore for multiple generations, etc.

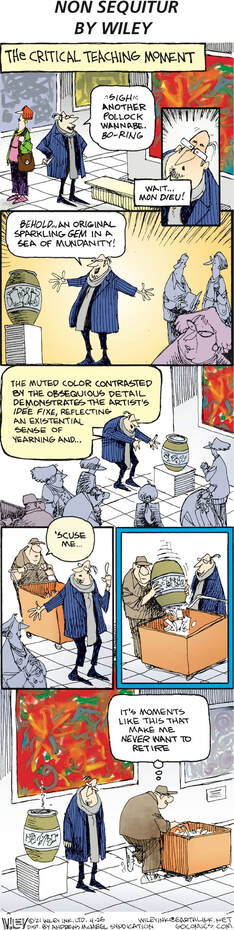

In any case, somehow this got me to thinking about the difference between a “critic,” as the term is commonly used, and an “expert.” This is not to say that these are mutually exclusive categories, although my experience is that not all people with actual expertise behave as critics and that not all critics actually have real expertise.

I would suggest that an “expert” is one who can examine something and provide some information about it, or at least have the ability to find such information in fairly short order. This might include some background about the person/group who created it; how it seems to relate to other works by that person/group; where it fits into recognized “schools,” or patterns of related works; some sense of its market value, if any; etc.

On the other hand, a “critic” is, all too often I have found, one who wishes to offer an opinion on the aesthetic value of a work and is likely to want to spend time and energy explaining why his/her opinion is more likely to be of greater value than yours in making such judgements. While I will admit that there are a great many people who know a great deal more than I do about a great many things, I dislike the notion that I am not supposed to be allowed to make up my own mind about what I prefer and what I don’t. I have always supported the old “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” idea and I really don’t care a lot if one agrees with me nor not.

I do believe that my own training and experience provides me with certain amount of credibility in offering opinions regarding some areas of dramatic literature and theatrical practice. I do NOT believe, however, that that expertise gives me the right to make determinations as to what you should like, or why. There are many plays by major playwrights which, I will argue, are in fact well-crafted and even important works, which I don’t particularly care for. I am fond of many of Shakespeare’s plays, for example, although I really don’t care much for Titus Andronicus and wonder how anyone could really care for this bloody tale. Although I should point out that I don’t consider it one of Will’s best. Nor is it considered a “great” play by a good many other people. That should NOT restrict YOUR right to enjoy it, if you wish, however.

In looking at scripts, or, especially, productions, for that matter, I like to use the critical ideas of Goethe as a guide. These can be summarized as: What is the writer (production) doing or trying to do? How well are these things being accomplished? Are these things worth doing? To me, these are the keys ideas of criticism, they have no specific relation as to whether I enjoy them.

I remember being taken to task by a student critic in The Carolinian when I directed Beckett’s Waiting for Godot because he didn’t feel that Didi and Gogo felt the appropriate “existential anguish” over their plight of being eternally “waiting for Godot.” I would suggest that we simply have different interpretations of Beckett’s intent. I believed, then and still do, that Beckett was NOT seeking the audience’s identification with their “suffering.”

When my student cast and I first read the play together, we discussed the idea that it seemed part of Beckett’s point that, like many humans, these characters were going through “life” without a real grasp of their status in the Universe. That is, their lives don’t seem to have any meaning because they don’t choose to actually DO anything except wait for someone else to provide some meaning for them. Hence, the point isn’t their “existential anguish,” (they, after all, are just bored with waiting) but the audience’s as it (hopefully) comes to realize that the Universe isn’t responsible for providing meaning for us; we have to find, establish, and define it for ourselves.

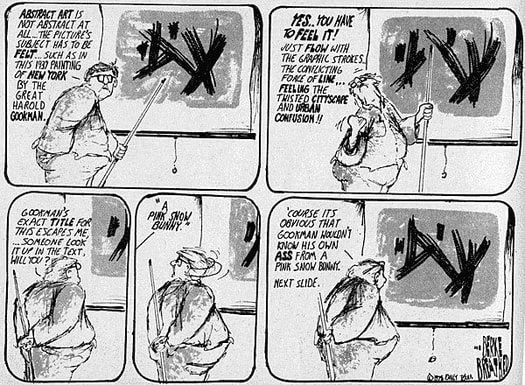

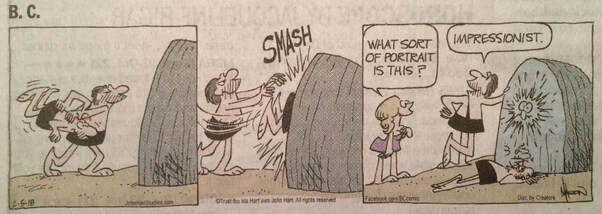

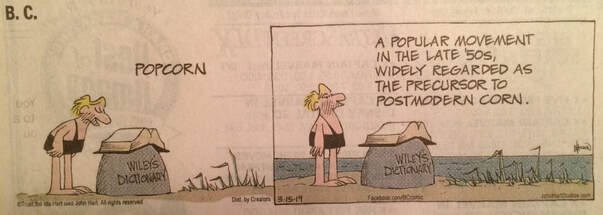

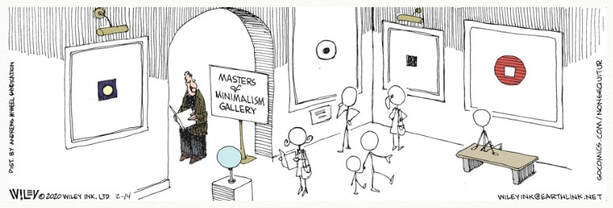

Still, apparently there are others who tend to join me in finding a certain amount of humor in the discussions of “critics” who want to sell us on the idea that they “know” something which we should desire, if we plan to be properly fulfilled human beings. Often this humor is expressed in the form of cartoons, of which I now present a few because I found them amusing when thinking about “criticism.” Most of these refer, primarily, to visual art because that tends to work better with cartoons, but the ideas do translate. Or I think they do. Enjoy.

More than once, while visiting an art museum, I have felt a bit like Earl in Pickles:

Dr. B

RSS Feed

RSS Feed